Life, Novels

ĐORĐO SLADOJE, A POET OF THE UNSWEETENED WORLD, TRAPPED BY INFINITY

It is important to be ready

So says Shakespeare: to be ready, that’s all. Since we’re already here. God himself saved us, I don’t know who else could. Childhood is our personal myth; from there stems my poetry as well. I’m not from the Nemanjić dynasty, like so many today. It must be that even the less glorious had some descendants. Whoever cannot laugh at the world, who cannot turn all the pain and hardship of life into a joke, will go mad. The world has dangerously tilted, and who knows where the pendulum will stop. Much will depend on the tragic war in Ukraine. And for those who still don’t understand how this world functions, how much hypocrisy and arrogance there is, it’s useless to explain. If they manage to take Kosovo and Metohija by this or that means, they won’t even ask us about the rest

By: Branislav Matić

Photo: Branislav Lučić

It calls for giving up on giving up. To some, it offers a home, to some a trail. It knows that none of them longs for massiveness but for meaning and succession. For the low fliers to thrive, the ladders have been lowered to the ankles. And he, for half a century, keeps a diary of insomnia, sings in the fog, and descends into solitude. He measures the distance of Hilandar and the weeping of Sava. In golden husks, in tremor, in a soul with seven layers, he seeks an everyday Tuesday and a Serbian mirror. He postpones the departure of the house keeper.

It calls for giving up on giving up. To some, it offers a home, to some a trail. It knows that none of them longs for massiveness but for meaning and succession. For the low fliers to thrive, the ladders have been lowered to the ankles. And he, for half a century, keeps a diary of insomnia, sings in the fog, and descends into solitude. He measures the distance of Hilandar and the weeping of Sava. In golden husks, in tremor, in a soul with seven layers, he seeks an everyday Tuesday and a Serbian mirror. He postpones the departure of the house keeper.

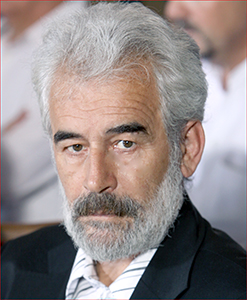

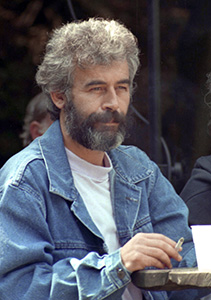

Đorđo Sladoje (Klinja, in Herzegovina, 1954).

Heavenly role models. According to both my father and mother and their parents and distant ancestors, I am a Herzegovinian, born in the most Herzegovinian part of Herzegovina, as Isidora Sekulić once wrote for Ulog. And now, when I say that I was born in the village of Klinja near Ulog, I fear that readers, even many Herzegovinians, will not understand anything. My geography is a bit tangled, as is my biography, for that matter. Ulog is a small town on the Neretva River (I jokingly say it’s the largest Serbian city on that river, where about fifteen inhabitants live today), situated in its upper course, where it is still small, but when it floods and goes wild, it carries trees and rocks and everything in front of it. Ulog is on the road between Nevesinje and Kalinovik and was a customs post during Turkish rule, as evidenced by toponyms such as Carevac, Carinik (customs officer), and others, as well as geographical maps dating back to the 16th century. Ulog is probably one of the oldest settlements in Herzegovina, on the caravan route from Dubrovnik via Mostar, Foča, Pljevlja, and beyond. Klinja is a hamlet, eight kilometers from Ulog, which had about twenty houses, roughly half Serbian, half Muslim. I walked from there every day, even on Saturdays, to school in Ulog. Today, I jokingly boast that I also attended a long-distance school.

As Jefto Dedijer writes, and he is the most reliable in ethnographic matters, my ancestors are originally from Žrvanj near Ljubinje, and initially, they bore the surname Paranos, which they probably changed when they ran out of money (pare). What kind of trouble forced them to seek refuge in Klinja near Ulog, will never be clear to me. I know they didn’t, as many boasted, kill a Turk in Montenegro, then flee to Herzegovina to save their lives and change their documents. This story jokingly told, doesn’t add up because if each of those fugitives had killed one Turk, the Turks wouldn’t have ruled for fifty years, let alone five centuries. Perhaps they sometimes turned against Serbs, but they didn’t have to flee because a Serbian head was cheap, and to this day it hasn’t significantly increased in value.

I also know that my ancestors were not from the Nemanjić dynasty, as written in the genealogies of many families that have been mass-published in recent times. Jokingly, I say that even during the time of the Nemanjićs, as always, there were poor and destitute people, and someone had to be their descendant. But no one wants to admit that. It will also remain a mystery to me how and where my ancestors came to Klinja near Ulog, so jokingly, I would say that we are the patterns of a heavenly people because one could only come up there from above.

Childhood, our personal myth. My childhood, like everyone’s, was exceptionally exciting, but sometimes burdensome, and even dangerous. As I mentioned before, I walked to school, and on that path, anything could happen – you could encounter some wild animal, snake, or a creature from a child’s imagination; you could fall from an old tree we climbed without asking whose it was until the owner chased us away; you could be carried away and swept by a suddenly rushing stream; you could slip off a log or get beaten by older and stronger kids if you weren’t fast enough. I defended myself from the stronger ones precisely with speed. It’s a wonder that nothing bad happened to anyone considering all the things we did and how far we got carried away in our excitement. God himself saved us, I don’t know who else could. We spent winters on handmade skis, sliding down steep slopes and often crashing into places so steep that you couldn’t even look at them without shuddering. As soon as winter passed, there was a ball game, that we could play for three long hours, and the game was interrupted when someone’s parents called them with a stern voice.

I spent most of my childhood outdoors, doing homework by the light of a kerosene lamp because electricity never reached the village, nor did a proper road, except for a horse trail. But the stars were bright and almost within reach, the moon enchanting, and the darkness so dense that sometimes it seemed to remember. And understandably, when you’re a child, all sorts of wonders and monsters can rustle from that darkness. They often scared me, so they instilled fear in me at some point, which, you won’t believe, helped me become more resilient to reality.

Childhood is, in fact, our personal myth – both in terms of experiencing time and space, natural phenomena, people, and things. In this mythical cocoon, you are in a completely protected and privileged part of reality, into which details from the adult world only occasionally intrude. Those first intense impressions, images, and scenes, deep experiences of the world as a great wonder, the intimacy with the whole, of which we are an inseparable part, even as a particle – all of that remains deeply etched in memory. As I age, all of this becomes clearer to me.

From unforgettable details. From the intensity and purity of emotions, from touchingly naive continuous wonder, a significant part of my poetry lives. I could comfortably say that it originates from childhood, or rather from memories of childhood. Since I learned letters before starting school, I loved writing some words with great excitement in the snow – with my finger or some stick. And then a snowstorm would blow and sweep away my manuscript, or when the south wind blew and the snow began to melt rapidly, my words would end up in some muddy pool. I realized early on how what we write easily and quickly disappears. And then, I started, I don’t even know how to effortlessly compose, or rather knit, humorous ten-line poems about village happenings, so the listeners laughed and enjoyed themselves until someone recognized themselves and got angry. And some wanted to beat me up, so I early on noticed that writing is not as harmless a job as it seems at first glance. Later, towards the end of elementary school, I switched to poems inspired by Vojislav Ilić, whose poetry I still love today. His winter and autumn landscapes are both accurate and suggestive, enhancing the experience of nature. Then, in high school, I began slowly to find my own voice, inevitably mixing with the voices of other poets whose poetry I was and remained receptive to.

In addition to poetry, football is my great obsession. I will never forget when my slightly older friend Milija brought a real football to play with, one with a bladder, which bounced like the devil himself, so we threw our balls made of rags into the bushes. One of the unforgettable moments, since you ask, is also when the raging Neretva river washed away the wooden bridge, so for some time, we crossed to school by boat. It’s hard to forget that force of water in front of which a man is completely helpless. Or, for example, herding cattle in the morning, and in the evening –mother is gone; she had a kidney attack, so they urgently, on horseback, sent her to Ulog, and then to the hospital in Foča. And everything suddenly becomes different – cold, empty, bleak, and in addition, cows don’t let anyone milk them because they are used to only her. And when she returned, even they rejoiced, not as much as I did, but I saw how even animals rejoice and give twice as much milk. Or that inevitable snow that used to fall around St. Demetrius’ Day, and in the best-case scenario, melt at the end of April, not to mention St. George’s Day. If you didn’t stock up on basic supplies, for yourself and the cattle, it was difficult. I say for the cattle too, because your survival depended on them, and it’s no coincidence that cows, sheep, horses... were treated almost like household members. Everywhere around, as far as the eye could see, everything was white, frozen, as they said, and on a clear day, it sparkled and didn’t let you look at yourself. Or in the evening, snow would fall, and those flakes were the only link between both worlds, especially with the upper one. I was even then convinced that those little snowflakes bring us messages from the Lord who wants to tell us that we are not alone amidst this white desert. And those evening snowflakes are one of the stronger metaphysical experiences that still overwhelm me today and take me back to childhood, just as the scent of elderflowers almost magically does. I can’t forget that mournful female song that girls used to sing at church gatherings and similar events and gatherings: Lively pine, you’re always young / And I am now, but never again... Or my father’s song ”with haunting sounds”, just like in Šantić’s enduring elegy...

There are many unforgettable details from childhood, but here I will still stop, believing that I have, at least partially, presented my case.

The plain. When I finished elementary school in Ulog, as one of the best students in its quite long history, my older brother was nearing the end of high school. For his education, our parents sacrificed everything, so the once wealthiest house in the village came down to two cows and a dozen sheep. There was almost nothing left for me, and further education seemed almost impossible. And then, from Banat, from Jaša Tomić, my aunt Zora contacted us and insisted that I must come to her. One more spoonful wouldn’t hurt anyone. Uncle Aleksa came for me, one of the mythical figures of my childhood, whose visits were true holidays, which couldn’t be said for this one because I was leaving home for the first time and wouldn’t return until the following year, as if I had been in the army.

The plain. When I finished elementary school in Ulog, as one of the best students in its quite long history, my older brother was nearing the end of high school. For his education, our parents sacrificed everything, so the once wealthiest house in the village came down to two cows and a dozen sheep. There was almost nothing left for me, and further education seemed almost impossible. And then, from Banat, from Jaša Tomić, my aunt Zora contacted us and insisted that I must come to her. One more spoonful wouldn’t hurt anyone. Uncle Aleksa came for me, one of the mythical figures of my childhood, whose visits were true holidays, which couldn’t be said for this one because I was leaving home for the first time and wouldn’t return until the following year, as if I had been in the army.

I remember us running to catch the train so it wouldn’t leave without us – it’s an innate fear that something beyond our control might slip away... They bought me some shoes with hard soles, so they clattered like demons chasing me. I woke up somewhere in Šid and stared out the window until the sunflower field began to spin like a giant carousel. As far as the eye could see, there was nothing to catch onto. That first impression that a person in the plain is completely exposed and thrust out with all their might, not only against the famous Banat winds, has stayed with me to this day.

The house I came to was large, Swabian, and first to the railway station. Half of my village could fit into it. When they first served me a burger, I almost choked – you could feast on it, not just half but the whole village. My cousin Nikola, with whom I would share a room for four years, asked me if I knew how to play football. I knew how to play, very well I might add, but I wasn’t sure if it was the same game in Banat and Herzegovina. They handed me the ball, and I immediately returned it to see what they would do with it. When I saw it was the same, we played heartily in the following days and years. To help me adjust to the plain, the new residents who welcomed me as their own helped, and my uncle Đuro was one of the best people I had ever met. At school – in the high school in Sečanj – I quickly adapted and made lifelong friendships with both students and teachers. When I won the first prize at the literary competition for high school students in Kikinda, it was a great and unforgettable joy in our small high school. However, I never fully got used to the plain, but I don’t dramatize it, and there are days when I don’t think about it at all. If the Creator, for some unknown reason, made it like this, it’s up to us to accept it since we’re already here. Those four years of high school and daily train and rail bus rides from Jaša to Sečanj will remain in my lifelong memory. I wrote about it, creating my small Banat mythology, which nicely complements the Herzegovinian one.

My second return to the plain, this time to Bačka, was forced by war, and the terrifying and nightmarish refugee years I wouldn’t want to recall publicly once again. May it never happen again to anyone.

Defense with humor. I often say, and I will repeat it here, that storytelling and humor in Herzegovina are existential, not stylistic categories. Everything that is lacking in real life, and almost everything is lacking, was compensated for by storytelling and narrating, which were invariably seasoned with humor. There are still those who can tell endless and fantastic stories, and this beauty of storytelling and fabulous linguistic richness goes hand in hand with the scarcity of life. Every single thing, every phenomenon, emotional state, and moral quality had not just one name but a multitude of synonyms. Everything, therefore, was named, or rather baptized, so, for example, a sheep was called Gramophone, in a mocking sense, of course, and someone even named their horse after the former American president Reagan. So, for instance, the poorest man is called the Sultan, and another who returned from the army with a peculiar accent is called the Northener because the northern wind blew constantly in Pančevo, where he served in the army and where he had the best time of his life.

Anyone who couldn’t turn all the hardship and burden of life there into a joke, such as I remembered, didn’t have a good time; such a person, as they would say there, would have gone mad.

It is clear that neither storytelling nor humor can fundamentally change reality, not even in Herzegovina, but they can make it more bearable. Of all the definitions of humor, perhaps the most accurate one is that it is the last defense of the powerless, although often, in a sense, it is a sign of intellectual superiority. Moreover, humor is an excellent purifier of banality, stupidity, and all kinds of shallowness on the one hand, and of pathetics on the other. And we lack neither one nor the other. There are too many gloomy people who take themselves and the world too seriously. Especially themselves.

Man is the only animal species given the gift of laughter, and it’s a pity that it is not used enough, regardless of whether it comes from God or from the devil, as some think.

The use of humor for literary purposes requires special attention and emphasis because it can easily slip into a pun, joke, or anecdote, which is not good for either prose or poetry. And there is a huge range – from invective, through irony, without which modern literature is unimaginable, to dark humor and grotesque, or the already proverbial laughter through tears. I learned long ago that not everything witty is artistically valuable. But that humor is precious both in literature and in life, there is no doubt. Those in Herzegovina know this, and those who write books and those who read them defend themselves by it, especially those who tell their endless stories and use them to dilute the bitterness of earthly life, trying to appease immeasurable forces, just as children do. After crying, a smile is a child’s first reaction to reality, to what seems daunting in its impenetrable hermeticism.

Only man is given consciousness, inevitably tragic, of transience and mortality. To accept and endure this inevitability more easily, we amuse ourselves in a hundred ways. Storytelling and humor, art in general, are some of the better and more interesting means to tame hell, as someone nicely put it.

About language and writing. Somewhere I’ve already written about how the Serbian language today resembles a robbed and impoverished peasant who was swindled at a big-city flea market. The beautiful and rich Serbian language deserves much more attention, care, and respect from those who speak and write it, but also from those who decide on the manner of its public and official use. Despite the great efforts of linguists, but also a significant number of writers, the Serbian language is daily being degraded, undermined, plundered, tortured, and rapidly impoverished before our eyes. And if we are already talking about violence in various forms, from peer to domestic and every other, it should be said that there is a peculiar violence against the Serbian language at play.

There are many perpetrators – from external ones, i.e., from our traditional enemies, to various organizations, and associations, but also those who should care about that language. Language is one of the key elements of national, cultural, and historical identity. It is no wonder that it is under attack by those who, while political noise lasts, work undisturbed and systematically on the dismantling of key identity bearers – language and script, cultural and literary traditions, history and mythology, education at all levels, and attacks on the Serbian Orthodox Church have become a common occurrence.

With the disappearance of villages and the extinguishing of thousand-year-old patriarchal culture, parts of the language of that world also disappear, and entire linguistic conglomerates are eroded – agricultural, fruit-growing, livestock-related, not to mention the language of old crafts in decline. The language simply has nothing to name or mediate, or rather, no one to serve. But this demographic decline is not just a linguistic problem, and it is no consolation that many others are faced with the same, I dare say, even the most difficult problem.

On the other hand, accelerated technological development, which delves into the very anthropological essence of man as we know him, and especially the improvement of means of communication, significantly impoverishes the lexicon of the Serbian language, reducing it to a mere means of communication and shortened, simplified information. And language is not just information and communication but an immeasurable field of creation. Hence it is no wonder that our students use only five hundred words from all linguistic wealth. If you want, you can see that there is a dismantling of Vuk’s language, from which all artistic, cultural, spiritual, and other contents and identity components should be squeezed out, to manipulate more easily in all areas of life.

Cyrillic is a separate story, and it’s such a problem that one cannot believe the extent to which it has reached. On the one hand, there is the indifferent attitude of the state, which did indeed pass a law on the use of Cyrillic but does not make an effort to implement it, and on the other hand, there is passive resistance from those to whom that law applies. It is inexplicable that Serbs voluntarily give up one identity-critical element, naively believing that they will appease the powerful by using Latin script and making themselves agreeable to their enemies. The persistence and intensity of suppressing Cyrillic exceed what is commonly referred to as the spirit of self-denial and auto-chauvinism. Such self-destructiveness certainly has elements of sociopathology, a kind of spiritual suicide. On the other hand, there is a law on gender language equality, or whatever it is called, which, without respecting expert opinion, was adopted in emergency proceedings, and for whose non-compliance drastic penalties are provided. In any case, it is a sad situation, I’ve already said, almost depressing. If we do not respect our language and writing, how will we defend it in other countries, where, quite understandably, it is unwelcome? Whether it’s about the remnants of Yugoslavism, which is more deeply rooted here than among other nations, or pressures from outside are such that we cannot resist them, or prejudices that Cyrillic is a less modern script, I couldn’t say for sure. But those who work under the motto Forget the past can be satisfied. Various associations for the defense of Cyrillic by Serbs often work clumsily, rejecting even those who would possibly use Cyrillic. Perhaps someone would even dare to write Cyrillic for their newly opened company instead of the obligatory ”commerce” and ”trade”.

Language has the ability to self-renew and self-fertilize, but without the help of those who should serve it, it inevitably fails. And nurturing one’s native language and script is a top-notch patriotic act, understood in the most beautiful sense.

After us, they wouldn’t even ask. While receiving the award Žička Hrisovulja in Kraljevo, about fifteen years ago, I said that there is not a single Herzegovinian Serb who holds himself in esteem, and whom the people respect, who has ever thought to, alongside Serbia, erect capitals along Herzegovinian hills. I want to reiterate here that for Herzegovinians, Serbia is the only country they yearn for and believe in. Many of them voluntarily came from America to fight in the Great War, not for Herzegovinian crags and valleys, but for Serbia and the fulfillment of the Kosovo Vow.

After us, they wouldn’t even ask. While receiving the award Žička Hrisovulja in Kraljevo, about fifteen years ago, I said that there is not a single Herzegovinian Serb who holds himself in esteem, and whom the people respect, who has ever thought to, alongside Serbia, erect capitals along Herzegovinian hills. I want to reiterate here that for Herzegovinians, Serbia is the only country they yearn for and believe in. Many of them voluntarily came from America to fight in the Great War, not for Herzegovinian crags and valleys, but for Serbia and the fulfillment of the Kosovo Vow.

An additional impulse to this integrative consciousness is the fact that Herzegovina is the land of Saint Sava, preserved in the national memory. And for me, Serbia is the Homeland in the fullest and most beautiful sense of the word, regardless of the fact that here, as a refugee, I experienced painful and difficult moments.

Serbia, for the umpteenth time in its rich and tragic history, is exposed to great temptations and unacceptable ultimatums, as it was before the First World War. Paradoxically, Serbs, in their ”Piedmont zeal”, liberated their Slavic brothers and worked on the creation of their countries more fervently than they cared for their own. The entire 20th century Serbia had spent outside of itself – yesterday in the name of Yugoslavia, today in the name of Europe. Already well into the 21st century, we still do not have a state with clearly defined borders. Against us, we have former allies from both world wars, who bombarded us with fury. Through propaganda machinery, they created and froze the image of Serbs as criminals and the main culprits for the collapse of Yugoslavia and everything that has happened in the Balkans over the past thirty years, ignoring the fact that Serbia gained independence, coerced, so to speak, only after all former Yugoslav republics became independent. Not to mention the attempts at revising and laundering history and producing post-truths through which it is commanded how it was and how it will be. God alone knows what this will lead to and how it will end. Or, as before, a ”frozen conflict” will remain in the Balkans, which can be activated at the whim of the powerful whenever needed. (...)

Serbia is truly in an extremely difficult position – internally disintegrated and externally pressed by ultimatum demands to relinquish part of its territory, in fact, itself. If Kosovo is taken from us or if we, by some unfortunate chance, give it away, they won’t ask us about the rest. I sincerely hope that this will not happen.

God, help the talented. Our cultural and literary scene seems quite gloomy and meager. Literary life, as I remember it, hardly exists or takes place only in circles and coteries of the most influential individuals. Magazines come out, mostly when they manage to gather money for printing, poetry books are printed in 200–300 copies, and even that remains without readers. On the other hand, the industry of cheap entertainment and surrogates of all kinds is flourishing.

Full steam ahead, openly and shamelessly, people look for self-interest, and ”on the high cellars” mediocre and bad writers have risen. Interestingly, some of the most significant cultural institutions are ran by writers who, with few exceptions, struggle both with talent and morality. They harness without hesitation all the resources of the institutions they lead and all the influence they have for their own affirmation. It’s enough to see where they were and how they were objectively treated before they got there. Thus, a false image of our literature is created, and the trouble is that some of the most significant critics, interpreters, professors are involved in it. Russians have a saying that goes: ”God, help the talented, and the untalented will figure it out for themselves.” And indeed, they have figured it out, only forgetting that literary justice is very harsh. Goethe says that a book that is propped up is a book that falls. Many praised, forcibly rewarded books, when the supports are removed, will fall exactly where they belong. Often, into oblivion.

Poetry, however. There is almost a general consensus that poetry has been the better part of Serbian literature for a long time. Prose is unable to break free from its own entanglements in which it has become ensnared, in its desire to be artistically valuable but also commercially viable, not to say mercantile. The biggest flaw of contemporary prose is its stylistic sloppiness and neglect of language, but it must be said that amidst the multitude of bad and mediocre works, there are a few good and very good novels, although they are hard to find amidst the flood of so-called light literature, whose production has proved to be very lucrative.

As for poetry, there is a noticeable diversity of poetic forms, thematic and motif variety, linguistic richness, and high literary literacy... There are, above all, books ranging from neo-verism poetry, through intimate to religious and so-called cultural poetry, while there are fewer and fewer authors dealing with historical and national themes. Free verse dominates contemporary poetry, although there is a considerable number of poets resorting to strict metered verse, which they ridiculed until yesterday.

The trouble with poetry is that it is read less and less; poetry books are sought only by rare bookstores, so even of those two hundred copies, many remain unsold. Sometimes it seems to me that someone decreed that poetry books are not to be bought or read. My impression is that poetry is read more than some would wish. The persistent repetition that poetry is in crisis seems a bit forced to me. As if only poetry were in crisis, when almost everything is, except that poetry thrives on crisis. It is obvious that literature, and therefore poetry, has lost its social significance and influence, so there is talk with regret about the ”Periclean era” of culture, when beginner’s books were published in thousands of copies, and reviews of poetry books were aired in the television news, and when more people attended literary evenings than today’s football matches. Poetry has, in fact, lost the ideological significance it had in socialism, while in societies without ideology, it has become unnecessary. Moreover, poetry raises uncomfortable questions to the world living on the surface, as a worker, sleeper, and consumer. And, importantly, it doesn’t bring profit, and everything unprofitable is marginalized. One of the most common questions I had to answer is – can poetry change the world? Poetry can symbolically give meaning to our lives, it can enrich them with beauty and harmony, linguistically and spiritually, but it cannot change reality. And I don’t know who assigned it that stupid role. All the power of the world is bent on changing the world, but both man and the world remain essentially the same, and the changes are barely cosmetic. Only the one who created it can change the world. But He, for reasons unknown to us, is still satisfied with His creation.

The literary, and even cultural paradox, is interesting – on one hand, the story about the crisis of the book never ends (many books have been written about it), and on the other hand, everyone writes – retired lawyers, judges, policemen, presenters, journalists, musicians, and movie stars... And until they write and publish a book, it’s as if they haven’t done anything.

Poetry will survive. I doubt that poetic revolutions like the ones carried out by Popa and Pavlović are possible today (although there were also other very deserving individuals, like Zoran Mišić), primarily because almost all poetic models have already been tried, including those of these two revolutionaries, so today’s poet can choose poetics by their sensibility. It should also be noted that such creative personalities are not born so often, unless someone somewhere deeply hides their talent, as Brana Petrović would say. Serbian poetry today undergoes an examination of poetic patterns in search of the new. And someone nicely said that there is nothing new in poetry, except for new talent. Perhaps this obvious return to tradition can be considered a kind of transformation that does not have epochal significance like that achieved by the great revolutionaries. However, it is interesting that what was considered a radical innovation seventy years ago fits perfectly into the traditional order of things. What tradition does not accept and adopt, does not actually exist. And changes in sensibility, however small, are always precious.

Poetry will survive. I doubt that poetic revolutions like the ones carried out by Popa and Pavlović are possible today (although there were also other very deserving individuals, like Zoran Mišić), primarily because almost all poetic models have already been tried, including those of these two revolutionaries, so today’s poet can choose poetics by their sensibility. It should also be noted that such creative personalities are not born so often, unless someone somewhere deeply hides their talent, as Brana Petrović would say. Serbian poetry today undergoes an examination of poetic patterns in search of the new. And someone nicely said that there is nothing new in poetry, except for new talent. Perhaps this obvious return to tradition can be considered a kind of transformation that does not have epochal significance like that achieved by the great revolutionaries. However, it is interesting that what was considered a radical innovation seventy years ago fits perfectly into the traditional order of things. What tradition does not accept and adopt, does not actually exist. And changes in sensibility, however small, are always precious.

I have no doubt that poetry will survive because there will always be those who must write it and those who wish to read it. It has never been widespread, but it is enough to keep the poetic flame alive even in the toughest historical winds.

If there is a home. I couldn’t say that I’m a great traveler, but I don’t resist traveling when the opportunity arises. I have been abroad several times and I don’t know what I would look for there again. I don’t speak with Americans and English people for political and geostrategic reasons, the haughty French wouldn’t even notice if I came, German sounds sharp and commanding to me, and I don’t like orders, especially German ones. There were two or three opportunities to go to Russia, but it just didn’t happen. And I’m sorry we probably won’t meet.

I gladly leave traveling to my daughter Tijana, who is unstoppable in that. In youth, there was no opportunity, and today there is no great desire or need. Sometimes it seemed to me, when I first came to a place, as if I had already been there. And maybe I have. While others spent their summer vacations, among other things, traveling, I was mowing. Because it would be a great shame not to help parents in that most important and most difficult job. But I don’t regret it.

I have happily traveled through Serbia, except for its eastern part, which is, they say, exceptionally beautiful. I have often been to Kosovo and Metohija, mostly for literary purposes, and I am very glad of it. I also believed that poems could appease our cruel enemies or comfort a distressed person. I love, of course, the areas beyond the Drina, regardless of their religions and nations.

Traveling brings the joy of new encounters, the illumination of beauty and divine creation, and acquaintance with other cultures and customs... For me, it enhances the sense of transience – now you’re here and who knows when again. Maybe never again.

In the end, traveling beautifies our return home. If there is a home.

The peculiarity of a place. In Novo Naselje, a neighborhood in Novi Sad where I live with my family, there are still trees and wide walking paths, unlike some other, mostly central parts of the city, where buildings tower over each other, in arbitrary, not to say incongruous construction. I most often take advantage of these amenities in the morning, making a fairly wide circle – to clear my head and collect my thoughts. Sometimes a verse comes to mind, and regularly I buy some basic household items. I enjoy that morning circular walk, and shopping doesn’t bother me either. Sometimes I grab coffee with a friend at a nearby café or come to watch a ”Red Star” game because I don’t have that sports channel. And I feel better when ”Red Star” wins, even if it’s in Surdulica.

Indeed, every place where we are in good health and good spirits with someone dear and important to us is special. Home is also an exceptional place and one of the greatest wonders that man has devised. And where, in these years, I still feel the best.

Masters. My first readings, admittedly oral and sonorous, were our epic poems that my father sang magnificently with the gusle. I don’t know how he remembered them, but he knew almost the entire Vuk’s anthology by heart, even some side poems. I will repeat here that I was, thus, early imbued with the decasyllable and illuminated by the Kosovo myth, which is our first and last, almost fateful story. And later, many of our, and also world masters left traces in my poetry. I have already mentioned Vojislav, but I could list a series of poets from Branko and Zmaj, Đura and Laza, to Dučić, Šantić, Rakić, Crnjanski, Dis, Desanka, Raičković, Kulenović, Danojlić, Bećković, Simović, Brana Petrović, and especially Duško Trifunović and Rajko Petrov Nogo. Duško liked to help young poets, in various ways, and I was among them. And Rajko, as my fellow countryman, convinced me in an exceptional way that our poor homeland is worthy of poetry. Interestingly, the poets of my generation and some younger ones knew by heart the poems of our immediate predecessors, but they also followed our development and knew how to encourage and support us. I cannot say for sure, but it seems to me that today’s young poets are in some kind of voluntary self-isolation and that they are not very interested in previous generations. I would like to be wrong. I forgot a few significant world poets that I read and still read with pleasure, in translation, and who influenced my poetry in various phases. So, many Russian poets, especially Yesenin, Blok, and Pasternak, then Yeats and Rilke, more English than French poets, then Spanish and Italian... All these are, therefore, poets who inevitably influenced my poetry, and I regret that I remained impervious to some good poets from whom one can learn a lot.

Walking Poetry. I used to create poems during solitary walks, and then I would diligently write them down and only slightly refine them, just enough not to spoil that initial impulse. And now I usually walk most of my poems, but I have to write them down immediately so that forgetfulness doesn’t erase them. However, now I spend more time on poems. Writing prose required full attention and concentration, and most of the time went into typing. Otherwise, I have no preconceived plans or demand special conditions. True, sometimes writing takes me out of everyday life and beyond my will.

I write with a pencil and then type it because that touch with paper is simply irreplaceable and everything is somehow at hand, while in the vast internet void, our text can easily get lost. Writing is manual labor and it is entirely possible that it will suffer the fate of old crafts that are disappearing. A good thing about writing is that no one forces us to write, except when something from within demands the appropriate linguistic expression. Then it’s important to be ready.

As Shakespeare says: to be ready, that’s all.

Hopelessness is a sin. Even though our reality resembles the end times, a person must, even instinctively, resist the general chaos and violence. Despite everything, we must hope that many things will change, and dangerous processes will turn towards a good outcome, although there is truly no indication of such. The world is on the brink of a major war between the most powerful forces. Americans, accustomed to being the masters of the world, find it difficult to tolerate competitors such as Russia and China. The war in Ukraine is much more dangerous than many that Americans have led and are leading around the world. It is evident that they are frustrated by Russian armed resistance and Chinese economic power. This is a clash of civilizations, as Huntington predicted – the Western (Anglo-American) and the Russian. The outcome of this conflict, which is difficult to predict, will largely determine the future of the world.

Amid powerful and divided entities, Serbia is today, and this today has lasted too long, in a difficult situation. Those who have ravaged and disintegrated it do not allow it to recover; rather, they try by all means to force it to voluntarily renounce the most important part of its land, because they have their national interest there, while we have no right to it because supposedly we persecuted Albanians. And there are more of them there just as much as there are displaced Serbs. These are the facts, but ”shame for facts.” No one cares that even the few Serbs there, are terrorized by Albanians in a hundred ways, that human and international law are being violated, if such a thing even exists anymore. I repeat – if they take Kosovo and Metohija in this or that way, they won’t even ask us about the rest.

But despite all this, Serbia has no right to perish, nor do we have the luxury of despair. Our spiritual life is based on the trinity of faith, hope, and love – the sanctity of life, so to speak.

Hopelessness is, after all, a great and hardly forgivable sin. Isn’t it beautifully said –hope is given to us because of those without hope.

***

Note

Đorđo Sladoje (Klinja, Municipality of Kalinovik, Srpska, 1954). He graduated from elementary school in Klinja, high school in Sečanj, and University in Sarajevo. He worked at the National and University Library in Sarajevo until 1992 when he fled from war to Vrbas, Serbia. Until 2007 he was the secretary of the Festival of the Youth Poetry and editor-in-chief of Trag in Vrbas. Since 2007 he has been the editor of the literary program at the Cultural Center in Novi Sad. He was editor-in-chief of Letopis Matice Srpske. He published more than twenty books of poems and poetry selections, among which are: Dnevnik nesanice (1976), Veliki post (1984), Svakodnevni utornik (1989), Trepetnik (1992), Plač Svetog Save (1995), Petozarni mučenici (1998), Daleko je Hilandar (2000), Ogledalce srpsko (2003), Mala vaskrsenja (2006), Manastirski baštovan (2008, 2009), Zlatne olupine (2012), Silazak u samoću (2015), Pevač u magli (2017), Odlaganje odlaska (2019), Modre žilice (2021), Dimni znaci (2023)... He also writes prose (Riba Zvana Gaovica, 2023) and essays.

He is the winner of over forty literary awards.

He lives in Novi Sad.